Playing Cards and Decans: Taurus II — The Six of Diamonds

See the master post on my 2024 decan walk and playing cards

Six of Diamonds

Six of Diamonds

Taurus II is the decan of Taurus 10° to 19° (inclusive). It is ruled by the Moon, in a sign ruled by Venus. It corresponds to the six of pentacles in Tarot, which further corresponds to the six of diamonds in playing cards.

The traditional English method divinatory meanings for this card are:

- Marriage early in life, succeeded by widow-hood.

- marks an early marriage and premature widowhood, but that the second marriage will probably be more unfortunate.

- Early marriage and possible widowhood.

- Early marriage and possible widowhood.

(These numbers start at 2 as the first source listed in the metapost doesn’t contain a delineation!)

Reflection

The Moon can signify changes and fluctuations, as it’s the fastest moving “planet” in astrology. It represents the individual corporeal body, alongside conception, motherhood, and (to list significations from Valens!) nurture, housekeeping, and living together. Valens further assigns it to voyages, travel, and wanderings, alongside expenses and gains — which I interpret as finances in the sense of household finances and management, rather than money itself. Venus also represents motherhood, alongside nurturing, but with an emphasis on love and desire of all kinds.

Between the two of them, we have love and travel, motherhood and pleasure. Both planets are of the night sect, with the Moon leading the night planet of Venus, so it is no surprise that we see the Moon “winning” in the end with this card, with the early wedding eventually disappearing. On a bodily level, the Moon is the breath, and Venus is the lungs. Venus contains the Moon’s breath within her lungs, which is eventually exhaled out.

“Widowhood” is the negative aspect of this card. It is not a divorce, but the possible death of the spouse. To reach into the astrological symbolism, the Moon represents the human body and change, with death as one inevitable change to the human body — although this is certainly one of those parts where the astrological and cartomantic symbolism diverges. You would not expect the Moon in exaltation in Taurus to represent possible early deaths of loved ones!

Let’s look at the Rider-Waite tarot:

Six of Pentacles

Six of Pentacles

Here we see distribution of resources. Fairness is implied, with the scales of justice, but it is not equal, with money only being given to one individual. This sense of non-equal justice is reflected in the combination of marriage and widowhood in one card: everyone receives their due, with both the joy of Venus and the inevitable changes that the Moon brings.

Peace,

⭕

Playing Cards and Decans: Taurus I — The Five of Diamonds

See the master post on my 2024 decan walk and playing cards

Five of Diamonds

Five of Diamonds

Taurus I is the decan of the first 10 degrees of Taurus.1

Taurus I is a decan ruled by Mercury, in a sign ruled by Venus. It corresponds to the five of pentacles in Tarot, which further corresponds to the five of diamonds in playing cards.

The traditional English method divinatory meanings for this card are:

- A settlement.

- Unexpected news, generally of a good kind.

- shows that you will have good children, who will endeavour to make your life easy.

- Unexpected news.

- Unexpected news.

Reflection

The connections of the meanings of the five of diamonds to the decanic astrological imagery are immediate. Receiving news? Mercury. A settlement? Mercury. Specifying that it is good news, and a good card for children? Mercury ruled by Venus.

Reading this card in reference to the decan almost feels too easy for the start of this decan walk journey. Let’s compare it with the Rider-Waite deck:

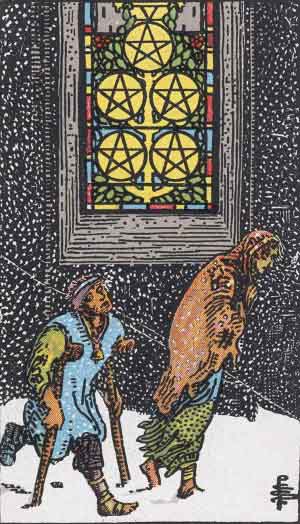

Five of Pentacles

Five of Pentacles

The difference here is quite stark: two people stumbling through the snow outside a stained glass window, and Crowley went so far as to emblazen “WORRY” as the title of this card on his deck. Unexpected news can be anxiety inducing, but anxiety relates more to the feeling of something coming round the corner, even if undefined. Worry about where one is going, or if those inside the building will let you in from the cold.

This can reframe “unexpected news”. Anxiety can arise when the unexpected is being expected — when the mind is occupied by all kinds of “what ifs” and other possibilities. The five of diamonds represents both that aspect of worry — news could be coming at any moment — but combined with the divinatory irony that because you have predicted the news, it is no longer unexpected. The Venusuvian character of the overall sign of Taurus comes through in this moment, much more explicit in the playing card than the Tarot card: the children will be good, the news will generally be good. Yes, the mind may induce all kinds of worries and fantasies about the future, but the ultimate arc of the five of diamonds tends towards the unexpected bringing goodness.

(Phew.)

Peace,

⭕

Yes, this also makes it the third decan of the zodiac. I’m starting these posts with Taurus I because that’s when I began this decan walk.↩︎

Playing Cards Through the Decans

Over on Base, we are going through a decan walk — contemplation on the 36 decans of the zodiac, as the Sun transits through them.

As I’ve been recently getting into playing card divination, I’ve decided to refract the decans symbolism through the lens of playing cards, looking at possible ways of reading the meanings of both of them through each other.

Playing Card Traditions

I’ll be using the “English” folk tradition meanings of the cards, ones that developed around the now-standard 52 card deck, rather than meanings associated with Tarot cards or piquet decks that developed in continental Europe.

This means the meanings of the cards are often very different from the imagery and meanings of their associated Tarot cards — something that makes them ripe for reflection!

It is extremely unlikely that the meanings of playing cards developed with any conscious reference to the decans, or even astrology generally — we are looking here at ✨ synchronicities ✨ rather than intentional meanings, nor am I claiming that the more literal predictions of some cards will occur while the Sun is in that decan (go watch the thread on Base, if you’re curious to see me relate these playing cards to my experiences).

The meanings are from, in order as given in each post:

- Phillip Breslaw — The Art of Fortune-Telling by Cards, 1784

- Robert Chambers — The Folklore of Playing Cards, in Chambers Book of Days, 1864

- Mother Bridget — The Universal Dream Book, c. 1816, in Donald Tyson

- Charles Platt — Some English Methods of Telling, c. 1920

- A. E. Waite — The English Method of Fortune-Telling by Cards, in A Handbook of Cartomancy, 1909

I found these through Donald Tyson’s excellent Essential Tarot Writings (2020).

Why?

There is no better way to get to know a divinatory symbol than to spend time with it. The decan walk will go through every card in the deck, except the court cards and the aces. This means that what’re often the “hardest” cards to understand and embody the core meanings for, the pips, are the focus of this contemplation.

Correspondences

The decan correspondences for the playing cards are those popularised by the Hermetic Order of the Golden Dawn, which are based on assigning Tarot cards to each decan. By corresponding the Tarot suits to playing cards, we can then easily find a playing card for each decan.

I’ll be using the most common set of suit correspondences, which matches with different styles of playing cards across Europe.

- Hearts = Cups

- Diamonds = Pentacles/coins

- Clubs = Wands/batons

- Spades = Swords

There’s a whole history to these things, but I won’t go too deep into them now, as the purpose of this exercise is to focus on the traditional verbal meanings of the cards in relation to the decans, rather than numerological or elemental correspondences (although those might come in!).

Posts

- Taurus I, the Five of Diamonds

- Taurus II, the Six of Diamonds

- Taurus III, the Seven of Diamonds

- Gemini I, the Eight of Spades

- Gemini II, the Nine of Spades

- Gemini III, the Ten of Spades

- Cancer I, the Two of Hearts

- Cancer II, the Three of Hearts

- Cancer III, the Four of Hearts

Peace,

⭕

Namu

The nembutsu, as recited in Japanese-derived Pure Land Buddhism, is namu amida butsu (南無阿弥陀仏), a Japanese rendering of the Sanskrit Namo Amitābhāya Buddhāya.

(Before we go on: in continual chanting it’s usually just “namu amida bu”, which rolls off the tongue easier!)

The first word, namu/namo, is of ancient heritage. Wiktionary very helpfully gives us the example of the ṛgveda passage 1.27.13, composed anywhere from 1500 BCE to 1000 BCE:

námo mahádbhyo námo arbhakébhyo námo yúvabhyo náma āśinébhyaḥ

yájāma devā́nyádi śaknávāma mā́ jyā́yasaḥ śáṃsamā́ vṛkṣi devāḥ

Homage to the mighty and homage to the lesser [gods]; homage to the younger and homage to the elder [gods]!

“Ancientness” is not a sign of good, but it adds flavour to the practice that is worth reflecting on. Nembutsu-focused Pure Land Buddhism began to differentiate itself in the 7th century CE, with the efforts of Shàndǎo in China taken as a key player,1 and a burst of activity in 12th/13th century Japan led to popular Pure Land Japanese Buddhism, which provided the impulse for my own practice.

The centring of the nembutsu in practice is a particular chain of interdependence: Sanskrit words are joined together, some from centuries before and some from centuries after the historical Buddha’s life, parsed into a Japanese phonology, then delivered around the world through preaching, books, and the internet.

Namu has literal translations stemming from namo’s connotations of bowing and reverence, but one of its main powers in contemporary Buddhism (regardless of who comes after the namu/namo) is in reaching towards a way of engaging with the universe that goes back thousands of years: through a verbal bow, using language to indicate and describe your ongoing act of giving reverence to something which is both other-than, and part-of, yourself.

Peace,

⭕️

But history is messy.↩︎

Blogging for the/a Spiritual Archive

In my “non-Circle” life, I have seen the importance of archives and records of peoples’ daily lives. Especially for religious movements that are small in whatever country or language they are being practised in, practitioners can fly under the knowledge radar.

Pure Land Buddhist practitioners in my country, charitably, number in the high dozens, split across a few different temples and traditions. In this regard, part of the impulse for me to blog about my way of being is simply for there be a representation of what an example of “Pure Land convert Buddhism” looks like in the early-to-mid 2020s.

This has become a stronger recently, as the Japan-based temple I attend remotely has stopped doing remote initiation ceremonies. These ceremonies are not ordinations, but essentially confirm the individual as being “on the books” and part of the organisation, as well as providing a spiritual benefit of dedication. The traditions of Pure Land Buddhism in my country that have active temples do not appeal to me for regular attendance (this is not for personal reasons, but simply because I have a very particular attachment to a specific tradition of Pure Land practice that has only a small reach outside of Japan). This has left me slightly adrift organisationally, but that has turned quickly to a sense of calm about the trajectory of my practice. I simply cannot, without getting on a plane (not impossible in the near future, though!), become a formal member of the lineage I currently most closely align with.

This is frankly, a relief. I can now freestyle. I can take the fragments of English-language (and as my Japanese skill improves, online Japanese-language) Pure Land materia that I have, and develop an independent way of being in the world. This is not completely anarchic—the sūtras and Hōnen provide axiomatic grounding for how I make decisions about how to practice and how to view. Yet my “home” is the practice itself, not an organisation. I do not have to be orthodox or orthopraxic, just true to where my existence is leading me.

This is why I consider a wider spiritual archive important—even if my own contributions to it are not particularly important or interesting. The way in which the dharma has navigated the West, producing syncretic and hybrid practices, is not due to a failure of Western practitioners to grasp a “true” Buddhism, but the way in which Buddhist practice inherently works—upāya includes the fact that full access to the nuances of traditions is fragmentary for many outside of particular countries where large organisations are based.

It is a truism that within each religious movement, no matter how big, each individual practitioner will have their own unique understandings and practices. Online blogs and other avenues for DIY publication provide a space for an ecology of archives to grow, away from the tenets of specific organisations, and back to sharing the lives created when the dharma begins to grow in someone’s way of being.

Peace,

⭕

On Peacemaking

In the contemporary druidry tradition, prayers, invocations, and rituals for peace are sometimes called “peacemaking”.

For perhaps obvious reasons (look at the date of this blog post, for those reading in the far future), peace is on many peoples’ minds, and I want to share some ways in which I attempt to grasp at this in my practices.

“Making”?

Like all concepts, the term “peacemaking” has connotations both beneficial for practice, and connotations that point away from particular possible ways of thinking about peace.

Peace making emphasises the real, practical, lived effort: peace does not come ex nihilo, it has to be planted, grown, and cultivated by sentient beings. This is particularly the case for peace within networks and ecologies (human or otherwise).

However, it belies one point that I see from my own perspective: peace as a state of being is always and already there, even if not visible and felt by yourself. This is “internal” peace, but I use that word with the awkward awareness of the oddities of interbeing and interconnectedness, where such an internal-external distinction eventually falls down. This peace cannot be made, but it can be discovered.

Peace-practice

The two methods of peace-practice here involve essentially “emanating” peace, in a verbal and visualisation pratice (either partially visualised, fully visualised, or just “felt” — all are valid).

Druidic — Ritual

The druidry tradition peacemaking ritual, as available to the public in the link above, has a few separate steps, but I highlight the first one.

Turn to the four directions and saying:

May there be peace in the North,

May there be peace in the South,

May there be peace in the West,

May there be peace in the East,

May there be peace throughout the whole world.

The similarities of this to loving-kindess or metta meditation will be apparent to some readers already.

This is currently my primary animistic-druidic practice. I tend to open my day with this, even if I don’t then go into a full druidic practice that early in the day.

While saying these phrases, imagining the direction (and then the whole world) being bathed in peace is crucial. Whether that visualisation is done for non-dual “magical” reasons, or for the psycho-spiritual effects on the practitioner is a separate question, but feeling the peace in more than words is crucial for this.

This can either be, as it is in my morning practice, under a minute long — a shower of peacemaking and peace-discovery. However, the ritual can be slowed down and performed over a period as long as needed, to deepen the experience of peace.

Loving-kindness — Meditation

Loving-kindness meditation is a popular Buddhist (and secularised) practice in the West, if not as well-known as mindfulness meditation. See the link just there for details, but the general approach is to generate feelings of love, compassion, and kindness, and then direct that at yourself, other people, and then the whole world (variations on this exist).

Part of this practice is visualising the world experiencing and being bathed in peace, as with the druidic practice above. However the peace-invocation phrase tends to be repeated, and they can vary from practitioner to practitioner.

I have integrated an explicit invocation of peace as part of my loving-kindness practice. I like keeping my loving-kindness practice simple, having only a few phrases which I can truly enter into and send out, so I tend to only have two or three that I repeat. Currently, they are:

May all beings live in peace,

May all beings be safe,

May all beings be happy.

I chose “live in peace” to emphasise both the internal and external aspects of peace. To energise all beings to “feel” or “experience” peace is a highly meritous act, which should not be devalued; however the current “““state of the world”“” brings forward engaged concerns about outward peace in terms of military actions, society, politics, and the climate.

“Live” emphasises continual existence within, and “in” talks about the situation around the being. Peace becomes a container, not just a state of being. May all beings live in peaceful containers, where they can be safe and happy with ease.

南無阿弥陀仏

namu amida butsu.

Peace,

⭕