Yijing Case Study: ䷐ Following and Missing the Point

Sometimes you just see auspicious and stop thinking.

Sharing case studies is one of the best ways in which diviners can improve community, and each other’s skills. I think that sharing failed case studies is even more powerful, as it allows one to see the holes in your own approach, and the approach of others.

The Query

I had just sent off a job application, and asked “How will this job application go?” and received what seemed to be a very positive cast.

Hexagram 17 (䷐ — 隨 Following), line 5 changing, with the resulting change to Hexagram 51 (䷲ — 震 Thunder).

Line 5, as the “prognostication” or key answer (following Zhu Xi’s method), reads as follows:

孚于嘉,吉。

Adler: Honest in excellence, auspicious.

Wilhelm: Sincere in the good, good fortune.

Hexagram 17 ䷐ is generally also very positive. The core hexagram oracle is:

元亨利貞,无咎

Legge: [Sui indicates that (under its conditions)] there will be great progress and success. But it will be advantageous to be firm and correct. There will (then) be no error.

The Interpretation

元亨利貞 is the formula found in the oracle line of Hexagram 1, and 无咎 is simply as Legge states — no error, no mistake. While the meaning of “元亨利貞” can be unpicked infinitely, Legge’s capturing of the four characters as ‘progress’, ‘success’, ‘firmness’, and ‘correctness’ are sufficient.

Line 5 seems also incredibly positive. 孚 honesty, 嘉 excellence, 吉 auspiciousness, great!

I hastily wrote down that this seemed positive, and interpreted this as meaning that the company would be impressed with my CV and cover letter, and (at least) give me an interview.

The Outcome

Oops.

I received a polite rejection email two days after sending in my application.

So what went wrong?

Re-Interpretation

I’ll come to a breakdown of the language of Line 5 shortly (and discuss intention in choosing a translation), but first let’s look at the context of Hexagram 17 ䷐.

Following Zhu Xi, I’m very much of the school that “the answer” is one of the moving lines (or a hexagram statement, depending on how many moving lines), but that it’s always coloured by and contextualised by the overall message of the hexagram. This is contained in the main hexagram oracular statement, but also in the hexagram name, and in the hexagram’s trigram and yin-yang coding.

Hexagram 17 ䷐, Following, has a very positive message, but only in the context where someone is following someone else.

The Image (one of the wings, or traditional commentaries) attached to the hexagram explains Hexagram 17 ䷐ somewhat cryptically as: ‘Thunder in the middle of the lake. The image of Following. The superior man at nightfall goes indoors for rest and recuperation’ (Wilhelm, edited slightly).

The Commentary on the Judgement wing starts with: ‘The firm comes and places itself under the yielding.’ (Wilhelm) — this is thus a rare case in the Yi, where the yin “yielding” line and the yang “firm” line are out of their usual roles, and so the usually-initiatory yang is actually following the usually-following-along yin line.

So, for the auspiciousness of the hexagram to manifest, someone had to be following someone else.

I’m the one sending the job application (initiating a process — a yang act, despite me being “yin” compared to the company). It was me who needed to be following.

Looking at the moving line:

孚于嘉,吉。

The first three characters can be understood more clearly in this context, in a way not fully captured at first glance of the English translations. 孚 is honesty or faithfulness, and while 于 can be “in”, in the sense of in a context or place, it can also mean towards something. 嘉 is that or those which is excellent, so another rendering in English could be:

Faithfulness towards excellence, auspicious.

This tightly matches the meaning of Hexagram 17 ䷐ as Following. I am to be faithful to, to put my trust into, and to follow the excellence of the company. That is what is auspicious — not my application!

Did I do that?

No — my job application was specifically framed around how I was a unique candidate, coming from an unconventional route to this position, and therefore special. I was positioning myself as an admirer of the company, but very much as a passionate, strongly individual outsider. Not a follower.

“Does this mean I have to learn Chinese?”

No, don’t worry.

I’m a firm believer in two things: first, that any knowledge of the Chinese of the Yi will massively improve your understanding of the text and it’s nuance, even if that’s just a short dive into the meanings of 元亨利貞, and checking Wiktionary every so often when there’s a difficult passage.

But, secondly, I hold that one’s available translations and intentions with those translations is how the Yi will channel itself to you, and it will moderate it’s message with the “awareness” (in a very… cosmic sense) of what translations you do or don’t have available. In some ways, I’ve snookered myself by getting further and further into the original Chinese, causing situations like these where ambiguous grammatical language like 于 requires me to come up with alternative translations on the fly!

But if you are sat there with a copy of the Wilhelm translation, read the Wilhelm and apply the wisdom and knowledge it presents to you.

Peace,

⭕

Music and Divination

I can’t quite explain why, but jazz and the Yijing go together hand-in-hand. Ambient electronic helps me understand the details of astrological charts, and anything upbeat keeps me focused on large cartomancy spreads.

There’s a tension in how people approach the environments wherein one does divination. At home, or even in a temple-like setting, many diviners across the spectrum are engaged in rather specific rituals — ranging from at least making sure you’re doing it on a clean surface, through to incense, candles, and prayers. Many divination textbooks tell us to treat oracular acts with such reverence. Even divinations that can happen “anywhere”, such as horary astrology, need a level of seriousness applied to them.

At the same time, many diviners have revealed utterly life-changing information to individuals at the base of some stairs at a party, in a small bedroom, while holding cards down outside on a windy day, or on a sticky coffee shop table, the list goes on.

Divination’s relation to its environment is a much wider question (quick answer: it depends on the system, and the diviner, ad infinitum), but it’s relation to music specifically has been playing on my mind.

I’ve noticed more and more that I’ve started to perform divination with music playing, without thinking about it. It’s not that I can’t divine without it, but putting an album on (and an album, not just a shuffled playlist!) has become a habit.

States of What?

A straightforward explanation of why music playing helps might be the idea of “states of consciousness” — Pharoah Sanders playing quietly while I re-read the same Yijing line will certainly have some kind of effect on my cognitive function. However, the fact that I used scare quotes there shows my scepticism (but, spoiler, I don’t think that’s wrong).

I generally try to avoid the psychologisation of “esoteric” phenomena. This is another blog post (or book) for another time (or life), but briefly put: I like to let divination speak for itself, and present its own systems of how it works. Applying late 19th century-onwards ideas of a singular brain that enters into “states” is different in many ways to all kinds of other understandings: animistic explanations of spirits delivering information, oracular possession, or even Jungian synchronicity.

As a rule of thumb: divination delivers us information. Any particular state of consciousness we enter into as we try to understand that information is a separate matter.

So what is it that music does when we divine?

A Divinatory Room

I realised, quite straightforwardly, that playing music does change me and my psychological state, but it also changes the entire environment.

The room becomes set for a specific purpose: while I’m using a phone and a Bluetooth speaker, the metaphorical equivalent of dropping a needle onto a record has started. Something has occurred, very intentionally, that is apparent to all in the room.

This is not necessarily a shift from an “ordinary” environment to a “sacred” environment. Often it can be sacred, but that’s usually a factor of the specific divination method (darkening lights to scry, rituals for spirit contact) than the act of divination itself (remember holding down Tarot cards to the table on a windy day?)

However, this is a still fundamental shift to a divinatory environment, from whatever it was previously — office, bedroom, coffee table slowly absorbing spilt cappuccino.

Navigating this shift is something that all diviners do, even when divining in rather un-reverential circumstances. A party Tarot reader trying to impart seriousness to an intoxicated guest may lower the volume of their voice, or get the guest to shuffle the cards and take a few deep breaths.

What Kind of Spaces?

Music fills the entire space instantly. On top of this, different pieces of music create different spaces. This allows us to think intentionally about the kinds of music we play, for the kinds of spaces we want to create.

It’s rare that everyone, in their day to day life, listens to Pharoah Sanders B-sides, or Four Tet tracks beyond what you find on Spotify playlists. Any piece of music that stands out — not a Lo-Fi Beats To Study/Chill To stream — will mark off the space as different. This does not mean it has to be music reserved just for divination, but anything that takes you out of “this is my office for sending emails” to “this is my boudoir for seeing the future” helps.

This applies even if you are just divining for yourself, or for a remote client — in fact, this is easier solo! Accommodating the musical likes and dislikes of others (to mention Pharoah Sanders again, sometimes that saxophone can be… too much) is more challenging than just scrolling through your collection and choosing something that changes your environment.

Feeling Like a Diviner

This ties into a crucial, but under-discussed aspect of being a diviner: that of being a diviner. “Diviner” is not a role most people in today’s Anglosphere understand or experience. For many of us, even professionals, it’s also not a role we do for more than a few hours a day — divination is part of the gig economy!

Anything that marks out a given space and experience as divinatory, even as opposed to other forms of spiritual informational exchange — meditation, counselling, coaching, ritual — helps the diviner understand their role in that moment as other, as delivering information for elsewhere (or from right here, depending on philosophy.)

Peace,

⭕

I’m Bad at Calligraphy

But I can tell that I’m bad, so that’s a plus. I got an idle (but still appreciated) comment on a Siddhaṃ oṃ, and I could see the sharp and strange curve of the tail, the inconsistency in the increase of weight from the left to the right side of the sky stroke, underneath the Moon dot.

But I can tell that I’m able to at least do “it”. Siddhaṃ calligraphy is such an arcane thing to pick up as a Westerner living on an island far away from India, China, and Japan. It’s not surprising for me to pick up, given my general life trajectory and the current movements of my Buddhist practice, but it’s… eccentric.

This gives me perhaps a space of grace, a “he’s doing his best” regardless of the actual skill or knowledge I have. Scratching together information from books and scant YouTube videos, I can’t be blamed for being bad, it’s not like I have a teacher whose valuable lessons I am simply ignoring in favour of brutish soft brush scrawl.

The practice is not calligraphy, here. The practice is not even just humility of “I’m bad!” — the practice is ensuring that I understand that being eccentric doesn’t mean I’m special. I need to maintain no desire to be an expert, be unique, or even be individual. Siddhaṃ is perhaps in some ways the ideal script for this, with highly regular forms established by historically key calligraphers, whose forms are to be learnt and applied. My goal is not to become a calligrapher, but to become someone who can let calligraphy happen.

Peace,

⭕

The “To Div” Note

What I optimistically call “woo admin” ends up being more of my practice than I care to admit. The time spent organising Yijing reading records and cooking up little Python scripts to regex search the plaintext for patterns is generally out of proportion with what I would like it to be. Maybe the aether will get me to write a post about that one day (and the unintended spiritual benefits of it, as sarcastic as I may be about my own time-sinks). But I want to mention one thing that has become key for my reflections, albeit in an unstructured way:

I have a “To Div” list, as in, things I want to divine about. While I follow the elaborate SADALKASTEN method for keeping track of my general life, this can be done on a pen and paper as much as in Obsidian.

It’s essentially a list of things one would like to divine about, but aren’t necessarily urgent. The trick is to note the dates when you think of all of these possible questions.

Comparing what you didn’t divine about — but felt close to doing — during a given period with what you did divine about1 is incredibly piercing for seeing what your real priorities are.

At the beginning of the year, my hobbies seemed key to me: I wanted to not just get back into various things that had previously brought me joy, but I wanted to excel at them. I have, unasked, floating in my To Div.md questions about the board game go 囲碁 and about music hobbies. What did I actually ask about? The mood of a friend going through a tough time, messaging old friends, and whether I should look for work in particular places. The disconnect between my intentions going into the year — games! Hobbies! — is compared with the beauty and challenge of reality, in messy relation with other humans with their own ups and downs and the realities of living in a human world determined by capital.

Ah well.

Peace,

⭕

Assuming that, like me, you regularly have an oracular practice such as Yijing, Tarot, or horary astrology, that you work with at least every few weeks.↩︎

The If-Will Continuum and Divinatory Shame

I’m making my way through Edward Shaughnessy’s The Origin and Early Development of the Zhou Changes, a rather masterful (and free to read!) overview of the history of the early Yijing. Shaughnessy engages in extensive discussion of the minute details of the language of the Yi, and does some great work in proposing interpretations and likely original intentions of key terminology, including the cryptic but moving 元亨利貞 yuan heng li zhen hexagram statement for the first hexagram 乾 Qian.

Of more general interest for diviners, beyond those obsessed with the early stages of written Chinese (although I would thoroughly recommend getting obsessed with the early stages of written Chinese as a light relief), Shaughnessy goes into detail breaking down how Chinese turtle-shell divination (卜 bu) questions were actually framed.

The question-asking paradigm for these diviners was developed inside a very different cosmology to contemporary Yijing diviners, but the questions share a lot in common with how many diviners I’ve encountered today formulate their questions. These questions also help illustrate a general issue I have with a false binary between “predictive” and “non-predictive” divination questions and systems.

I haven’t got the laptop battery left to scour through Shaughnessy’s book for exact page references (and hey, one reason I started this blog was to avoid having to be too academic! — but a lot of this is contained in Chapter 2 for the curious), but the process Shaughnessy presents for asking questions questions of turtle-shell divination, which followed through to later milfoil divination, is:

The diviner would state (or ‘affirm’, 貞 zhen) a ‘charge’ or ‘command’ (命 ming1), which was the action that the individual (in the case of recorded turtle-shell divinations, usually the Emperor) was going to undertake. The prognostication of whether the action will be successful or a failure, auspicious or inauspicious, would then be determined by the diviner. It is possible that the auspiciousness of the action was enmeshed in an animistic world-view, wherein the diviner was more directly asking if the action would have the backing of spirits (whether specific ones or the spirit world generally) — backing that would naturally be auspicious!

This is very similar to one of the most common contemporary Yijing question formats: “If I do such-and-such, what will happen?”

While these questions are (usually) less about going to war, the principle is the same: before an action is taken, the querent seeks to know if it will be successful.2

I’ve encountered, sometimes indirectly, comments by Yijing readers to the effect of it being less “predictive” than other divination methods — often presented as a virtue, as the Yi focuses the querent on broader topics of personal development, morality, and spiritual action, rather than simple “fortune telling”. Yet it is clear that these are still predictive questions that seek a predictive answer. The answer does not (necessarily) predict whether or not the querent will do the action in the question, which leaves open a spot for free will, but such a spot is contained within even the more “predictive” systems.

Horary astrology is the best example for this: questions for horary are generally framed as clear cut “What will happen?” or “Will such-and-such-a desired event/outcome occur?” However, contained within these are heavily implicit ifs. “Will she marry me?” is a predictive question, but it relies on a series of assumed actions taken by the querent — “If I continue to be in a relationship with her, and eventually propose, will she marry me?” is simply a more specific version of “If I continue to be a relationship with her, what will happen?”

There are many divination questions wherein there are almost no implicit ifs, except maybe an “If I do nothing, what will happen?” — asking about bureaucratic processes which are making decisions about the querent but are out of the querent’s hands are a good example, such as the querent asking if they will get a job after a job interview has been finished. There are further actions that could be taken by the querent to affect the outcome, for example, throwing their phone into the ocean guaranteeing they will not get a call-back, but these are unlikely. The “What will happen?” element is stronger in these questions.

All divination questions contain both a “hard” predictive aspect of laying out what will happen once a certain course is taken (or how an existing course will play out), alongside an aspect of interaction from the querent, to varying degrees. I call this the “If-Will Continuum”, which sounds like a bad sci-fi show, but it’s a useful heuristic for understanding how divination questions are formed across systems. More-so, this allows you to analyse your own questions for reflecting on what ifs and wills you are asking about.

This dispels the idea of “non-predictive” divination — even if the question is concerned entirely with internal personal growth and decisions made by the querent, it is still predicting something about the outcome of those actions or growth, otherwise asking the question is useless. Even extremely abstract divination questions, such as asking for a symbol to meditate on, involve some kind of predictive work: at the very least, the assumption that the symbol to meditate on will be in some way useful for the querent.

But why is dispelling this idea important? I have the feeling that among divination practitioners, particularly newer ones, there can be an element of shame regarding asking predictive questions. Many introductory books, perhaps well-intentioned, perhaps wanting divination to be taken more “seriously” by people who might not believe claims to its reliability, emphasise divination as a tool for personal growth, and will sometimes go as far as trying to separate out the proper use of Tarot, Yi, astrology (etc.) from “fortune-tellers” or “simple” cases of trying to “just” tell the future.

But in practice, we are all trying to tell the future — what differs between us is only which futures we dare ask about.

Peace,

⭕

Playing Cards and Decans: Cancer III — The Four of Hearts

See the master post on my 2024 decan walk and playing cards

Four of Hearts

Four of Hearts

Cancer III is the decan of Cancer 20° to 29° (inclusive). Astrologically, it is ruled by the Moon, in a sign ruled by the Moon.

The traditional English method divinatory meanings for this card are:

- A marriage bed.

- Domestic troubles caused by jealousy.

- shows that the person will not be married until very late in life, and that this will proceed from too great a delicacy in making a choice.

- A person near you, not easily convinced.

- A person not easily won.

Reflection

I’m opening this post directly with Agrippa’s image for this decan:

in the third face ascendeth a man a Hunter with his lance and horne, bringing out dogs for to hunt; the signification of this is the contention of men, the pursuing of those who fly, the hunting and possessing of things by arms and brawlings

This puts forward my key association of this card: the lunar hunter. Moon is stacked on Moon, accelerating both the moist emotional intensity of the Moon, and its swiftness.

Breslaw, Source 1, our oldest written source from 1784, simply lists ‘A marriage bed’. But soon we get to jealousy, and then a structure of delay and decision. A person will get married late, due to indecision, and will not be easily convinced or won over. Whether this is the querent or the questied, the joining of two will only come about after some time and convincing. There is a pursuit and a physicality to this card, something that requires strenuous movement. Unlike Cancer II and the Three of Hearts, with its implications of infidelity, this almost feels like a hyperfidelity — a dogged pursuit of a goal, even if it causes troubles.

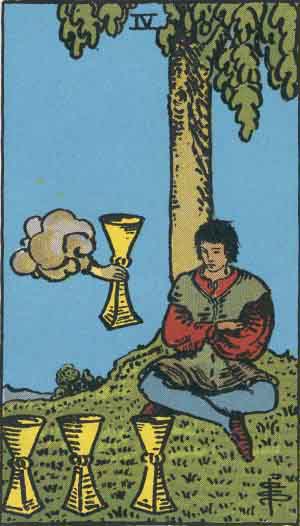

The Rider-Waite Tarot’s image is a lot quieter than this sounds:

Four of Cups

Four of Cups

Yet the focus is here. The figure is looking at the cups ahead, in a process perhaps of decision paralysis, introspection, or overthinking.

Peace,

⭕